The Walls Are Talking

Joachim Trier clearly thinks a lot about how people connect. His international breakthrough, 2022’s The Worst Person in the World, co-written with Eskil Vogt, follows one woman through her twenties and early adulthood’s many starts and stops. He expands this perspective in his latest, Sentimental Value, turning from one woman’s growth to the story of a house and the many generations of the family that has inhabited it. Earnest but never saccharine, Sentimental Value vividly explores how people relate to each other, the spaces that shape them, and where those meet.

Returning to work with Trier, Renate Reinsve stars as Nora, an anxiety-riddled stage actress mourning the recent death of her therapist mother. Raised in a beautiful dragestil (meaning “dragon-style”) home in Oslo, Nora and her younger sister Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) weathered the storm of their filmmaker father’s sudden departure in their adolescence, growing into (apparently) successful women with fulfilling careers. The film is, in a sense, narrated by the house, flashing through generations of its residents while an unnamed narrator reads from an essay about the house by a school-age Nora.

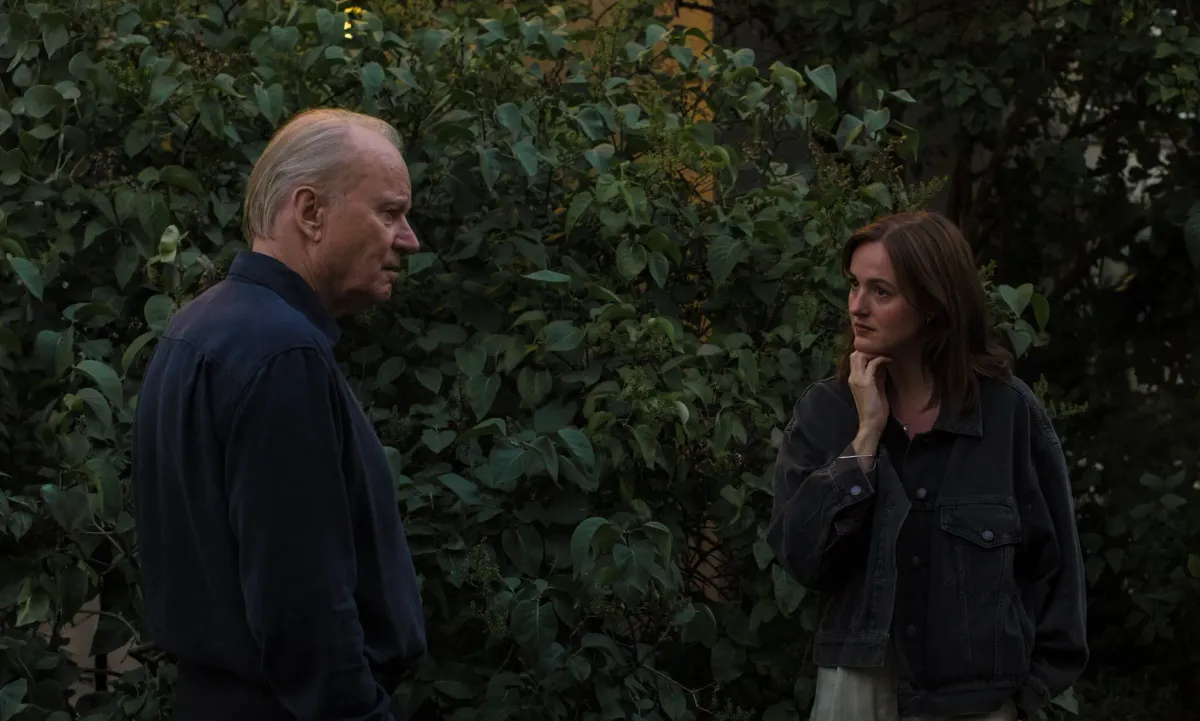

While Agnes remain close with their father Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård), he and Nora are essentially estranged, reuniting at her mother’s wake. The house has passed through generations of Gustav’s family that we come to know in some of the film’s most haunting tangents, and still technically belongs to him. While Nora and Agnes’ mother lived and worked there until her death, they simply never finished the paperwork. His appearance at the wake is no tearful reunion, as Nora and Gustav exchange pleasantries and he invites her to lunch. At that terse lunch, Gustav reveals that he intends to use the house for his next film, and he has written a lead role for Nora.

Nora tells Gustav, “we can’t work together, we can’t even communicate”, shutting down his hopes of making the film. This confrontation is a showcase for Trier’s observational powers; here, Gustav’s faulty ability to connect with Nora meets with Nora’s repulsion at working with him. Gustav thinks very little of the theater, and hasn’t had the time to watch the TV procedural Nora stars in. Reinsve perfectly embodies a central tension of the script, the push and pull of her innate need for his approval, which is complicated by her removal of herself from the medium of film and therefore his attention.

While attending a film festival retrospective of his work, Gustav meets Rachel Kemp, a successful American actress frustrated with the quality of her projects. After a night of drinking, Gustav offers Rachel a part in his new film, the very role he wrote for Nora. Rachel joyously accepts, unaware that she is now entering his fraught family dynamic. Elle Fanning does excellent work as Rachel. A lesser script and a meaner actor would have painted Rachel as the vapid American tainting into the Borgs’ refined Nordic air, but Rachel is a serious person, albeit a touch adrift in her success. Trier is concerned with the diffuseness of an artist’s life, specifically how success and fulfillment are completely different things.

Gustav is a celebrated filmmaker, but he’s been blocked for years, unable to emotionally cough up what he needs to. This avoidance, as is the case with the best family dioramas, is also Nora’s avoidance. She sells out crowds with expressionistic takes on classic drama, but the panic attacks she has before, during, and after shows indicate that she’s missing or running away from something. She tries to fill that void via an affair with a married actor in her company (Anders Danielsen Lie, returning to the Trier rep company after The Worst Person in the World), but her avoidant tendencies keep even the fun of a fling at arm’s length. When Rachel and Gustav show up at the house while Agnes and Nora go through their mother’s things, Nora quickly dashes out the garden gate and runs home.

It feels almost beside the point to try to appraise Reinsve’s performance. She is extraordinary to watch, Nora’s anxiety and remove conveyed with small gestures and a stiff upper lip. You can read everything on her face, and all of it rings true. As Nora and Gustav reestablish contact, she and Skarsgård get some excellent two-handler scenes. In these moments, you totally understand their estrangement. They see so much of themselves in each other, something Gustav wants to cultivate and Nora wants to forget. As he and Rachel start working together, Gustav tries to fill in the gaps of his and Nora’s relationship, a heartfelt attempt that never lands. After a conversation with Nora and some faltering rehearsals, Rachel realizes that this part simply won’t work for her. Once again, to Trier, Vogt, and Fanning’s credit, Rachel is not a diva as she leaves. With humility, she bows out of the project, leaving Gustav and Nora to face each other head-on. Meanwhile, as Gustav visits with past collaborators to get them to join the project, he begins to grapple with his age and mortality. A visit with an old cinematographer friend lets on that his drive to get this film made has a greater significance than he lets on.

Trier’s visual style is spare and light-filled, the perfect canvas for the film’s performances to live on. He uses negative space and close-ups much like John Cassavetes, keeping the audience in the moment for almost unbearably long amounts of time so they can read what’s printed on the cast’s faces. Some black-and-white and period-dressed interludes set in the house’s past deviate from the established visual language, but only so much that we are situated in those moments in time. Also like Cassavetes, Trier uses music sparingly, which makes the needle drops all the more impactful. The film’s coda, set to Labi Siffre’s “Cannock Chase” feels sudden and euphoric, like the storm depicted in the song.

The performance that holds the whole thing together is Inga Ibsdotter Lilleeas’ subtle work as Agnes. Unlike Nora, she truly has her shit together, with a partner and child as well as a stable relationship with Gustav. She is the family referee, which Lilleaas expertly lets the audience know has been the case for a while. It’s also notable that she’s a historian, compiling information on Gustav’s family in order to uncover what has been left out of the family record. The film’s climax is a beautiful scene between Nora and Agnes, an empathetic confrontation where the dam breaks. Like the rest of the movie, it’s emotional but never trite, and is perhaps one of the great tributes to sisterhood on film. Trier and Vogt are asking, who could ever know you better?

I won’t go into too much detail about Sentimental Value’s finale, an excellent piece of metatheatre calling back to one of Gustav’s biggest ambitions for his film. In these last moments, Sentimental Value reveals itself to be about how art is the only real way for some to communicate, despite how frustrating that is. Our worst blocks can sometimes only be worked out when we learn to speak each others’ emotional language first. Sentimental Value is an incisive, funny, and bittersweet slice of life, one where we can learn about ourselves simply by peering into the lives of its characters.