The Revolution Will Be Handmade

A performance by Bread and Puppet Theater, the legendary troupe out of Glover, Vermont, is always a singular experience. Their ramshackle, proudly political performances have been a linchpin of America’s protest theatre movement for over 50 years. Their show at Chicago’s Clarendon Park this past Tuesday, part of Our Domestic Resurrection Revolution In Progress, (co-presented by Haymarket Books and Pilsen Community Books) was performance as politics at its best. Founded in 1963 by Elka and Peter Schumann in New York, Bread and Puppet has always stood out for its Living Newspaper format and anti-imperialist stance. All these years later, Bread and Puppet still presents something wild and raw, truly political art in a time where that term is used in reference to things like Hamilton or The West Wing. That sort of political theater simply stages political discussion, dramatizing differences of opinion and gazing at how amazing the American patchwork of views is. Earnest fence sitting is far from Bread and Puppet’s forte. Their agitprop performances focus the audience’s gaze squarely on the injustices of the world, making no bones about the threats to dignity faced by humanity.

Tuesday’s performance began with the pep and energy of an archetypal circus show, only for the music to drop out. Two of Bread and Puppet’s white-clad performers stepped forward, hoisting placards reading “Gaza is Starving” and “End the U.S.-backed Genocide”. These deviations in form, embraces of stillness amid the joyful chaos, are in no small part why Bread and Puppet remains electric a half-century into its existence.

The touring ensemble sings and monologues in English, Spanish, Arabic, and Yiddish, dons costumes and swaps instruments throughout the show. They also operate Bread and Puppet’s astounding large-scale puppets and expressionistic masks. The show, alternating between comic sketches about grandmas, figurative dance interludes, and songs about how to keep ICE out of our communities, swing wildly from a tonal perspective without feeling out of place. The jauntily sung refrain of “Don’t say anything/Don’t sign anything” and the elegiac mime scene of a Gazan mother represented by a masked performer fit together seamlessly.

The show’s intentions of solidarity with all oppressed people are distilled in the grand finale, as the ensemble waves massive banners of Palestinian poppies. Bread and Puppet trains the audience’s eyes on the most urgent issues of our time, urging us to speak out the best way we can. By speaking so astutely to their own alternating senses of mockery and horror at the late-capitalist hellscape of 2025, Bread and Puppet invokes the audience’s sense of fear and pity just as the Greeks did centuries ago.

The overall message is one of revolution, one built by hand and in steady progress. In a group chat with some friends who are all artists in a variety of disciplines, we frequently agitate ourselves about the place of art in a world on fire. The consensus that we’ve come to many times is that art isn’t necessarily important in and of itself when it comes to politics. Yet, as Bread and Puppet shows us, art’s importance is contingent on the meaning that its creators ascribe to it. From its roots in the Vietnam protest movement to today, Bread and Puppet’s art has always kicked and screamed, imploring its audience to work for a better future.

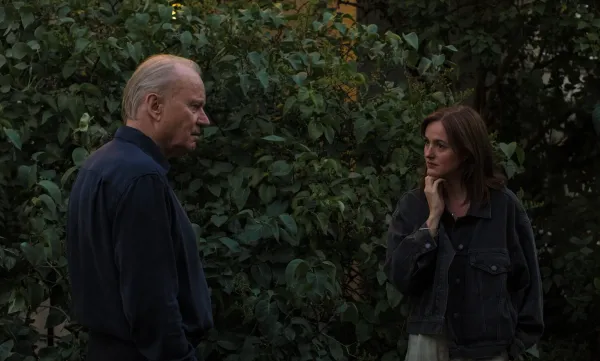

After the show, as I stood in the park flanked by Bread and Puppet’s signature prints and attendees eating homemade sourdough rye and aioli, I felt the immediacy of the Domestic Resurrection Revolution In Progress. By turning its audience’s head toward the miseries of the moment, whether through clownery or seriousness, Bread and Puppet paints a way out for us all.