Boys Will Be Boys

Friendship, Tim Robinson’s first feature film, is much more than just an extended sketch. Written and directed by Andrew DeYoung, the film effortlessly weaves huge laughs with a true sense of despair, the story of one man’s bleak existence ruptured by his inability to understand male friendship.

Craig Waterman (Robinson) lives in a nondescript suburb in a sterile split-level with his wife Tami (Kate Mara) and son Steven (Jack Dylan Grazer) and works at a company that makes apps more habit-forming. He gets all his brown-beige clothes from one company, Ocean View Dining. When a package for his new neighbor Austin is mistakenly delivered to his house, Craig (who appears to not have any hobbies or friends) and Austin initiate classic male bonding rituals. Unfortunately for him, and fortunately for the audience, Craig manages to fuck them up at every possible juncture.

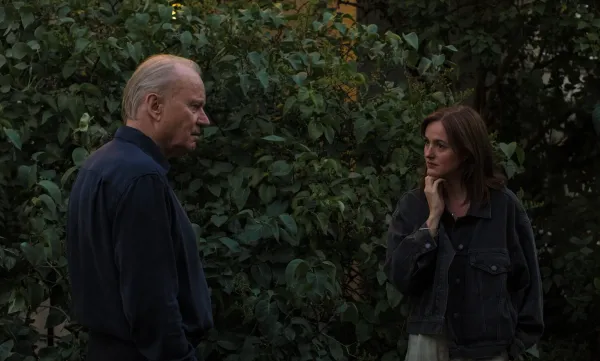

Austin, played by Paul Rudd, is a dumb guy’s idea of a smart guy. He plays in a rock band whose name, Fuck You Seth Nichols, is a message to their town’s mayor. After Austin waxes poetic about his prehistoric hand axe, a Roganesque monologue so deep that it leaves Craig with a nosebleed, the two become fast friends. The relationship gets deep quickly, not necessarily because Austin encourages it, but because Craig simply doesn’t know the right way to make friends. After Austin curtly cuts Craig out over a faux pas, Craig returns to his previous life, confused about what just happened. “You made me feel too free,” he pleads to Austin.

I can not overstate how dull Craig is. On Detroiters and I Think You Should Leave, Robinson’s characters are typically happy idiots who fixate on the wrong thing in a social situation and end up overreacting just to save face. Craig, meanwhile, is somehow charming in his blankness, endearing himself to the audience even as he continues to debase himself. For him, friendship is a process of emulation and obsession, an erotic drive to reshape himself in his new pal’s image. When he buys a drum set so he can jam with Austin and his band, you can almost feel how much credit card debt he has put himself in just to get close to Austin.

Rudd’s lowkey approach to Austin is an excellent contrast. He continually leaves the histrionics to Craig, like a reactive dog’s owner ignoring their pet to get it to stop barking. But Austin’s laidback confidence masks something much shallower, as indicated by an extraordinary piece of physical comedy from Rudd late in the film. Austin is only secure in his attachments because he knows the rules of engagement.

DeYoung, who wrote the screenplay (although I would be surprised if Robinson or his writing partner Zach Kanin didn’t punch it up), shared that Friendship was inspired by his own experience getting kicked out of an all-male friend group. We empathize with Craig because he is an outsider looking in, something rendered literally in shots of Craig looking through his office window at his alpha-male coworkers on a smoke break or through Austin’s sliding patio door at a friend-group hang.

There has been so much hand-wringing lately about how to fix lonely men, but Friendship posits that some men can’t function socially because they need instructions for making friends. When Craig returns to his life post-Austin, his solitary life appears so bleak that I half-expected him to join up with a local white nationalist gang. But Craig is likely too mild to join (or be welcomed into) such a group.

Friendship’s preoccupation with the rules of making friends is a legitimate issue when you consider how much American masculinity is rooted in projecting rugged individualism. Craig is no John Wayne, however. One of his greatest accomplishments is getting his own office so he can have whatever he wants for lunch. A less well-considered script could have become tiring at a certain point, but Friendship remains engaging throughout because the film’s conflicts remain as stupid as possible.

The film’s aforementioned bleakness is supported by all of its aesthetic choices, from Keegan DeWitt’s uneasy synth score and Andy Rydzewski’s cinematography to its supporting cast. Kate Mara, whose career is primarily comprised of heavyweight indie drama performances, brings a beautiful credibility to Tami that mixes surprisingly well with Robinson’s style. DeYoung has also populated the cast with comedians like Carmen Christopher, Jon Glaser, and Conner O’Malley, performers who have built their careers by playing nightmarish versions of “regular guys”. Whitmer Thomas, as Craig’s work nemesis Ian, is perfect as a blank-eyed alpha male.

The astonishing thing about Friendship is that, at the end of the film, you still root for Craig in spite of his countless failures. That’s the kind of thing you can only have by way of an excellent lead performance and a well-considered script. Ultimately, I was going to be an easy mark for Friendship, as I have loved and written about Robinson’s work for years. But putting aside that affinity, Friendship deserves to be celebrated for what it is: a kind of comedy that rarely gets a wide release these days, one equally comfortable with both broad, stupid laughs and psychological drama.